THE PROJECT, in three stages:

I wanted the world’s best toolbox for 21st century teaching. One of those magical vessels that heroic characters so often seem to have — a backpack, a quiver, a metaphor — that the rest of us can’t seem to quite find.

I came to Ohio State’s Digital Media & Composition Institute in May 2014 looking for lots of things. I wanted immersion in composition technologies and practices that I’d never used before: iMovie for video, Audacity for sound editing, iBooks Editor for digital publishing, Oxygen for XML markup. Along the way, I had the chance to steep myself in a rich set of digital humanities and compositions texts, many of which were multimodal themselves in form. Cindy Selfe and Scott DeWitt, along with an excellent team, led rich discussions each morning that opened possibilities and problems including:

- Creative Commons, the public domain, and plagiarism in a digital age

- “optimistic reciprocities” at a time when students navigate many more audiences than composition generally acknowledges

- tensions of multimodality and disability

- issues of technology and classroom design

- which approaches can productively shift in a writing program after designing a MOOC

- technology and the modern writing center

- first-year writing online

- digital activism’s intersection with composition, journalism and humanist scholarship.

I came to DMAC most especially for a community of like-minded peers, and it was a pleasure to discover the exciting work being done by faculty and graduate students at a number of universities across the country. It was also fun to watch them agonize along with me, late into the afternoons or on the muggy van ride to the hotel or grumbling in the lab on a Sunday, as we composed and revised our own 90-second multimodal projects, using recorded sound, video and images.

In the end, I also discovered with a kind of “duh-piphony” [Cindy’s term] that, for me, bringing multimodal composition back to my teaching and my university would mean weaving the two strands of my formal education: the academic and the creative writer. And a clearer path emerged.

—

I.

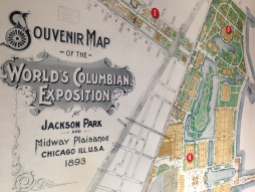

My first project looked like this:  I became fascinated with the 1893 World Fair Exhibition at the Field Museum, on a layover to DMAC that lasted 24 hours in Chicago. I wasn’t sure why I was so intrigued. I did, however, have a lot of footage, so even before I’d set foot at the Institute, I knew what I wanted to do.

I became fascinated with the 1893 World Fair Exhibition at the Field Museum, on a layover to DMAC that lasted 24 hours in Chicago. I wasn’t sure why I was so intrigued. I did, however, have a lot of footage, so even before I’d set foot at the Institute, I knew what I wanted to do.

Now if I were talking a student, I would’ve said: excellent, a moment of fascination. But pause. Why this set of evidence — are you ignoring anything else around you? [Like, oh, all of Columbus?]

But I had this amazing audio file I made on the Chicago elevated train! How could I not use that?

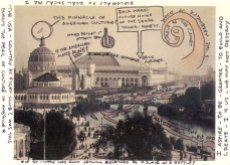

And video footage of the first Ferris Wheel, in 1893, turning. Only the video itself was impossible.  Cinema as we know it hadn’t really begun. I started to research Edweard Muybridge, the ‘father of cinema’, to see if such techniques were even possible.

Cinema as we know it hadn’t really begun. I started to research Edweard Muybridge, the ‘father of cinema’, to see if such techniques were even possible.

The Field had animated a few photos, but made them move with excruciating stillness. They hired actors to be green screened into photos from 1893, pre-cinema, perambulating on promenades as they took in the industrial and cultural displays. And that was interesting. The Field animated the images in a subtly multimodal way that made me question my relationship to old artifacts that feel inescapably from another time.

So: It was a Chicago adventure, I had all of these assets already, and with several canceled flights and flooding and barely escaping the cots being set out for stranded passengers in O’Hare… The romance of Chicago was upon me.

So: It was a Chicago adventure, I had all of these assets already, and with several canceled flights and flooding and barely escaping the cots being set out for stranded passengers in O’Hare… The romance of Chicago was upon me.

No idea, just yet, but that was okay. I was about to learn how to shoot and record and edit and compose.

—

II.

My second version, still focused on the Field Museum exhibit and its curation, looked like this:  Ideas began to form.

Ideas began to form.

The Fair was a site of wonder, but it was also commercial by nature: you could buy anything displayed there, from machinery to dinosaur bones to rare cultural artifacts.

I was trying to grapple with the role of Franz Boas: trailblazer in anthropology though his insistence that you needed to understand a future by being embedded to understand the context — yet he brought Inuit to such a miserable situation in Chicago that they sued.

I also wanted to understand how African Americans were largely barred from the six-month long event except for one day. And on that day, Fredrick Douglass came despite being warned not to, so he could give a speech on fairly obvious inequities in the Reconstruction era.

It was too much. Try speaking for 90 seconds: what can fit in that space? Wonders, multitudes. But not this. Not here.

So now what?

—

III.

Eventually, the more I really looked around me at the interesting work being explored and shared, I knew I had to reboot. It was time to acknowledge the fact my Field interest would need a different form and platform to really be satisfying.

When my students abruptly shift course, I encourage them to remember it’s part of the process, that all of that “wasted time” is the only way sometimes to get to where you need to be. That didn’t make my own frustration any less palpable at feeling like I had to start over.

I went for solitary walks in Columbus after course discussions and training sessions. And while walking, I kept noticing public art: sculpture and graffiti murals and cartoons and alt-culture stickers on walls and neon signs. I looked around as an outsider at this place where I’d be embedded for two weeks, and remembered Baudelaire’s notion of the flaneur.

It was at this point that I really understood that constraints were my friend. In 90 seconds, I needed one concept, one anticipated rebuttal, limited narration.

And so I turned to the most interesting images from the Field, as well as my experience being stranded in the airport for two days and wandering through Columbus during off hours from the DMAC Institute, and pondered the value of productive loneliness. How you’re forced to really step outside your own comfort and notice the cultures in front of you.

I remembered Baudelaire but also Walter Benjamin on the flaneur.

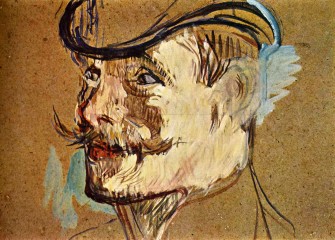

I thought of one of my favorite photographers, the Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson.

And then I considered how I’m always drawn to public art, especially street art, in new places. I wondered why that was.

So I spent a day gathering assets up and down High Street in Columbus. This included video interview of a cheerful drunk named Hill Billy from West Virginia who insisted on being shot in front of a large mural. And then we talked about his home, and how great the people were here, and his brother in Columbus sick with lung cancer. And we were both quiet, and I thanked him, and we shook hands, and I kept walking and listening and trying to really look.

The script got pared down and then pared down some more.

I thought of Scott McCloud’s notion of the gutter between comic panels: what can the audience understand without having to be told it?

I found music via Creative Commons searches. I located a few additional images, including Baudelaire and Benjamin, plus an illustration of Teju Cole. I took a trip, on another day, to the Columbus Museum of Art, and found unexpected convergences in the Toulouse-Latrec exhibition and examinations of the dandy in portraiture.

And I thought: I need to acknowledge how privileged Baudelaire’s artist is, with the economic freedom to simply walk around experiencing the world. But also, the poet isn’t wrong.

For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world. — Baudelaire, 1863

Lastly, I added footage of my 2-year old cousin negotiating public art in Dublin, Ohio — most especially a field of giant plastic corn — because how can you not? It’s comedy gold. Recording voiceover took time and intense effort — mainly with editing and mending consistency and timing, as I synced with beats in the music and flow with the structure of the images. Also: everyone hates the sound of their own voice over big padded headphones. Everyone.

Recording voiceover took time and intense effort — mainly with editing and mending consistency and timing, as I synced with beats in the music and flow with the structure of the images. Also: everyone hates the sound of their own voice over big padded headphones. Everyone.

When the deadline arrived I remembered, like my students, that the project isn’t done — it’s simply due.

We screened my film, along with the work of my DMAC Fellows, in Cindy Selfe’s backyard [on the grounds of an Edwardian zoo! New topic!], projected up against a white sheet in the summer night.

And the bridge work between writer of fiction and creative nonfiction began to make more sense with my role as an academic committed to the work of digital literacies. These needn’t be dichotomous identities with firm church/state divisions. Multimodality means using every tool you’ve got, every blessed one, as you analyze and engage the world, while empowering students to do the same. That sounds about right.

–

As such, for your multimodal pleasure, I submit to you my final Concept in 90 piece for the Digital Media & Composition Institute: The Flaneur.

Enjoy!

-Ryan Sloan

May, 2014